Hyperledger Incubates the Indy Project to Address Identity Management

Importance of identity management

“On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog,” reads the caption on an iconic cartoon panel from a cartoonist Peter Steiner in The New Yorker in the 90s.

Therein lies the problem a quarter century later. Identity and its management have become an enormous pain to individuals and organizations alike. Now, a new Hyperledger incubation, referred to as Indy, aims to address and solve the problem.

Indy has been incubated by Hyperledger and is described as a set of “tools, libraries, and reusable components for providing digital identities rooted on blockchains or other distributed ledgers so that they are interoperable across administrative domains, applications, and any other silo.”

Indy was incubated with code from the Sovrin Foundation, a non-profit organization formed in September 2016 with the aim of using distributed ledger technology to create “self-sovereign” identity management. The Sovrin code was, in turn, originally developed by Evernym.

Hyperledger has now incubated eight tools, a list that also includes Blockchain Explorer, Cello, Composer (another new incubation), Fabric, Sawtooth (previously known as Sawtooth Lake), Iroha, and Burrow. Here’s the Indy incubation proposal.

Power to the people

In its essence, self-sovereign identity puts the control of the Internet identity in the hands of users rather than organizations. Sovrin’s efforts are part of a movement to end three decades of control by website owners to the services they offer.

Today’s prevailing approach requires individuals to establish a login with every website, which they wish to interact with—whether Facebook or Twitter, Amazon or any place they shop, government agencies, and increasingly, media companies. Thus, as we all know, we can have dozens of logins as part of our web life.

This approach means either we have:

- Dozens of separate logins and passwords (for the 1%, who are careful about this sort of thing)

- The same login and password (keeping things simple but thereby creating honeypots of access for the thieves, who break into customer lists)

- That maddening mixture, in which we have several slightly different logins and passwords to meet the varying login requirements (thereby complicating our lives while still creating significant honeypots).

The so-called “adhesion contracts,” in which the companies, not the individuals, establish the rules of the game, are another annoying aspect of this tradition. A bigger problem with the approach involves a steady march of break-ins into customer databases and the credit card information stored there. Additionally, the system is massively duplicative and inefficient, with thousands of organizations required to keep their own silos of data about millions of the same customers.

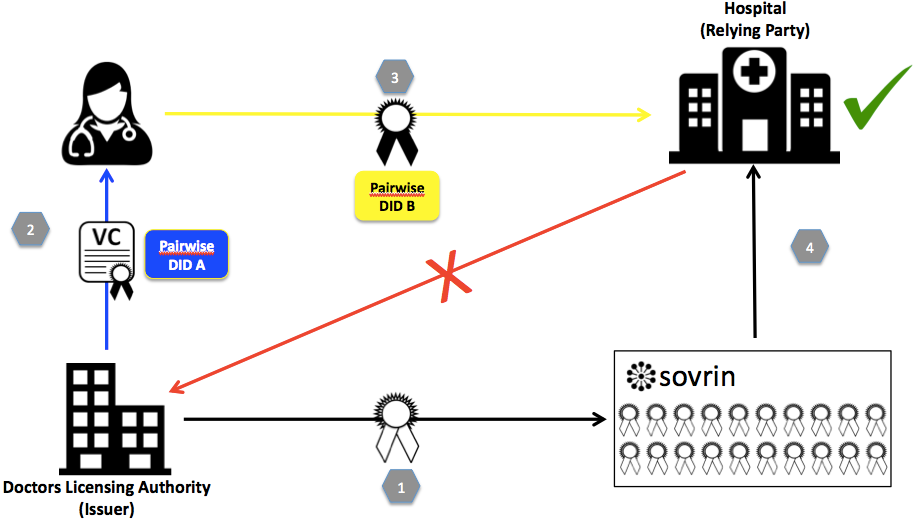

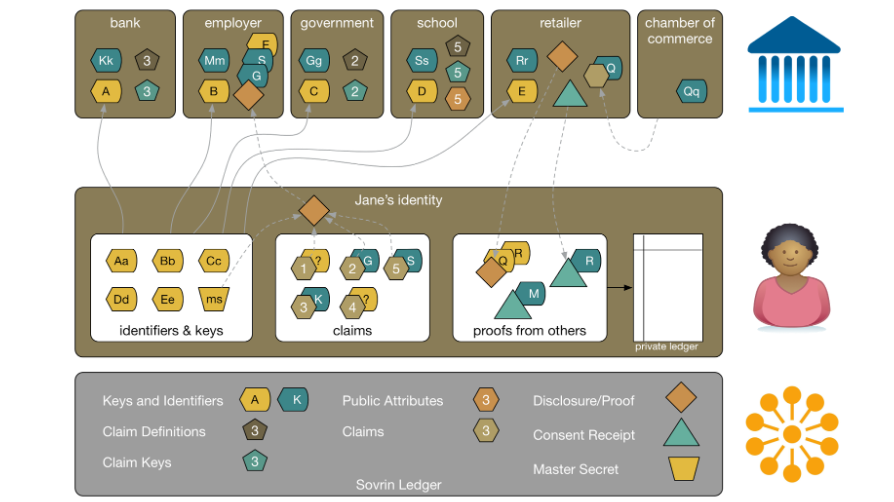

A typical example of a verifiable claim interaction (Image credit)

A typical example of a verifiable claim interaction (Image credit)According to the Sovrin Foundation, 30 to 40% of contact center call volume relates to password and account recovery, and 25 people per minute in the US alone become identity-theft victims.

Is self-sovereignty inevitable?

None of this is new or particularly shocking information. We all know the current system is antiquated and leaky. The question is, what can the Indy project do about it?

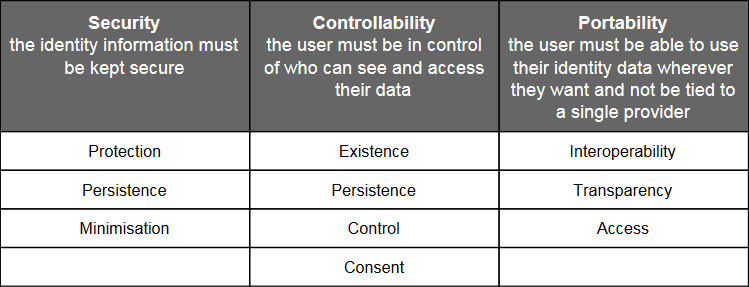

In one of its white papers, “The Inevitable Rise of Self-Sovereign Identity,” the Sovrin Foundation makes several big points, stating that “the evolution of the Internet identity is the result of trying to satisfy three basic requirements:

- Security. The identity information must be protected from unintentional disclosure.

- Control. The identity owner must be in control of who can see and access their data and for what purposes.

- Portability. Users must be able to exploit their identities data wherever they want and not be tied with a single provider.”

Other excerpts reveal more of the organization’s thinking.

“To create the long-missing identity layer of the Internet, a new, trusted infrastructure is required, which enables identity owners to share not only identity, but also verified attributes about people, organizations and things, with full permission and consent.” —The Sovrin Foundation

“For identities to be truly self-sovereign, this infrastructure needs to reside in an environment of diffuse trust, not belonging to or controlled by any single organization or even a small group of organizations.”

“The distributed ledger technology is the breakthrough that makes this possible. It enables multiple institutions, organizations, and governments to work together for the first time by forming a decentralized network much like the Internet itself, where data is replicated in multiple locations to be resistant to faults and tampering.” —The Sovrin Foundation

A new public, permissioned blockchain

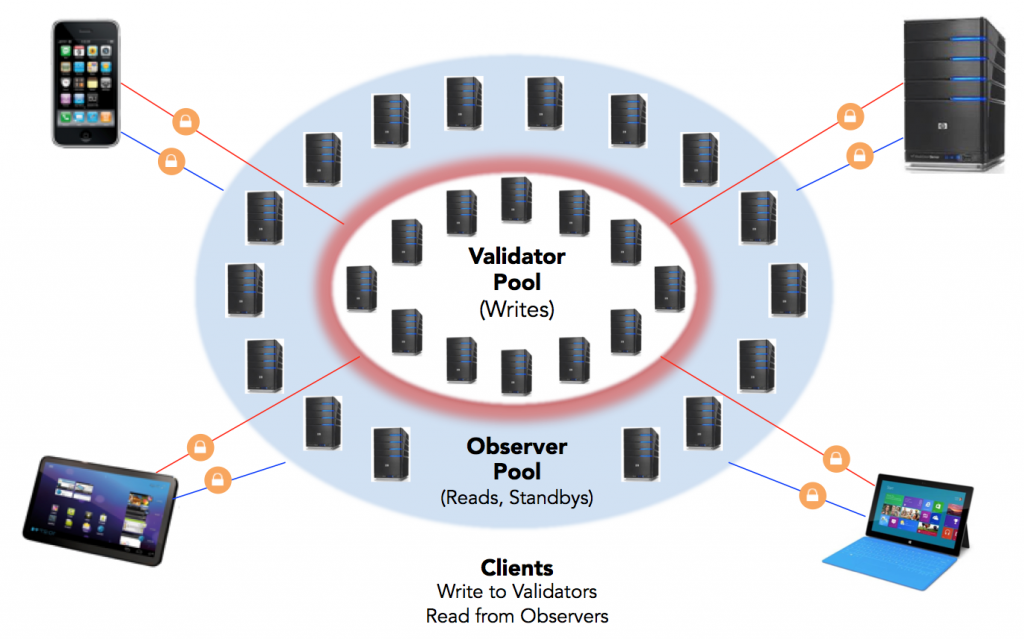

Sovrin, and Indy, propose a “public permissioned” blockchain system. This is a new but, perhaps, inevitable idea. It stands in contrast to public and permissionless systems—that is, anyone can join without exception (permission). It also stands in contrast to Hyperledger Fabric and other blockchains that are private and permissioned—networks that are formed by a group of members, who regulate who can join and what they can do.

The Indy public permissioned network is open to all, and it is the individual that gives permission for his or her identity to be validated. Additionally, the Sovrin Foundation controls transaction validations within the ledger at this point, and now the Hyperledger Project will develop the distributed ledger technology into a blockchain-based project.

Indy deployment achitecture (Image credit)

Indy deployment achitecture (Image credit)

Who should control permission?

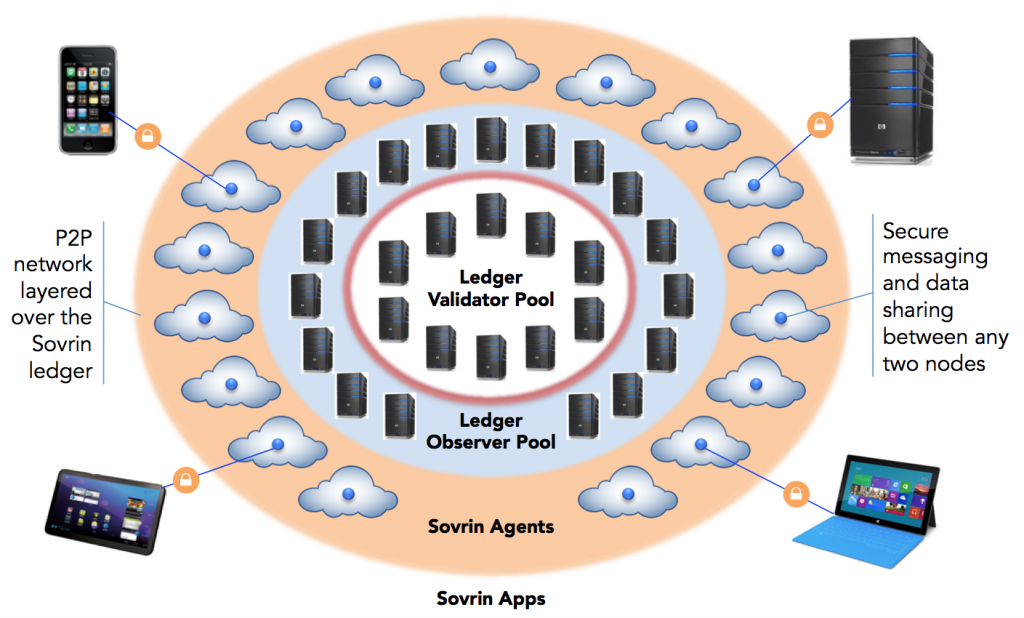

Personal data is not written to this ledger, but exchanged only over peer-to-peer encrypted connections off of the ledger. As with other blockchains, the ledger is a metadata repository that only “anchors” encrypted data, providing immutable proofs that transactions occurred.

“Open, decentralized systems enable individuals to fully own and manage their own identities, leading to the idea of “self-sovereign” identity systems, according to the “Private-Sector Digital Identity in Emerging Markets” white paper by Caribou Digital Publishing and the Omidyar Network.

“These systems use the combinations of the distributed ledger and encryption technology to create immutable identity records. Individuals create an identity ‘container’ that allows them to accept attributes or credentials from any number of organizations, including the state, in a networked ecosystem that is open to any organization to participate (e.g., to issue credentials),” according to this paper.

“Each organization can decide whether to trust credentials in the container based on which organization verified or attested to them; in other words, a mortgage company may accept a credential issued by a leading global bank, but not the one issued by a local bank. Importantly, this model does not require a state-based credential to be initiated (the state credential can be added at a later time, or not at all), which removes a barrier to adoption.”

Indy’s peer-to-peer off-ledger agent interaction (Image credit)

Indy’s peer-to-peer off-ledger agent interaction (Image credit)Again, the key point in all this is that individuals, not organizations, control the permission.

Decentralized identifiers are key

Phillip J. Windley, Chair of the Sovrin Foundation, wrote an intro for the Hyperledger Project about what to expect in these early days of Indy.

“Not only can Indy support user-controlled exchange of verifiable claims about an identifier, it also has a rock-solid revocation model for cases, where those claims are no longer true. Verifiable claims are a key component of the Indy’s ability to serve as a universal platform for exchanging trustworthy claims about identifiers.” —Phillip J. Windley, the Sovrin Foundation

The word “claims” is a big one in the world of identity management, and refers to whatever an individual is trying to prove: name, date of birth, other personal information, occupation (i.e., whomever or whatever the person is claiming himself or herself to be or have). Its use can often be thought of as the same as saying “credentials.” A typical user will make several claims to several organizations, but unified in a single identity that the person controls.

Image credit

Image credit“Identifiers on Indy are pairwise unique and pseudonymous by default to prevent correlation,” Phillip also wrote. “Furthermore, Indy is the first distributed ledger technology to be designed with decentralized identifiers (DIDs) as the primary keys on the ledger.”

“DIDs are a new type of a digital identifier that were invented to enable long-term digital identities that don’t require centralized registry services. DIDs can be verified using cryptography, enabling a digital ‘web of trust.’ DIDs on the ledger point to DID’s Descriptor Objects (DDOs), signed JSON objects that can contain public keys and service endpoints for a given identifier. DIDs are a critical component of the Indy’s pairwise identifier architecture.” —Phillip J. Windley, Sovrin Foundation

However, Sovrin and Indy are distinct with Sovrin being a specific, operating instance of the Hyperledger Indy code that contains identities that are interoperable at the global scale. While Indy is a code development project, by contrast, “Sovrin is an operating network—a living ledger, in which each node is running an instance of the Indy project’s code.”

To stay tuned with the project’s evolution, sing up with the Indy’s mailing list.

Built upon earlier principles

Christopher Allen of Blockstream confirmed to us that he was part of the DID design team. He has headed the Hyperledger Identity Management Working Group for the past year, and is one of the most prominent voices in this field. Among his extensive writings on the topic, he outlined ten principles of self-sovereignty:

- Existence. Users must have an independent existence.

- Control. Users must control their identities.

- Access. Users must have access to their own data.

- Transparency. Systems and algorithms must be transparent.

- Persistence. Identities must be long-lived.

- Portability. Information and services about identity must be transportable.

- Interoperability. Identities should be as widely usable as possible.

- Consent. Users must agree to the use of their identity.

- Minimalization. Disclosure of claims must be minimized.

- Protection. The rights of users must be protected.

“An identity system must balance transparency, fairness, and support of the commons with protection for the individual.” —Christopher Allen, Blockstream

The aspects of the ten principles have been captured in the following table by the Sovrin Foundation.

Image credit

Image creditWe can imagine that these principles will be part of the Indy effort, as this identity-management incubation now becomes integrated into the entire Hyperledger community.

Other Hyperledger incubations

- Hyperledger Incubation: Burrow Integrates Ethereum Virtual Machine

- Hyperledger’s Sawtooth Lake Aims at a Thousand Transactions per Second

- The Iroha Project to Bring Mobility to Blockchain with Simple APIs

- General Availability of Hyperledger Fabric v1.0: What to Expect in 2017 and When?

- Hyperledger’s Fabric Composer: Simplifying Business Networks on Blockchain